STAR TREK

�AND THE

HISTORY OF THE CHURCH

— Introduction —

The outrageous but bizarrely supportable thesis statement that I lay before you is this:

| |

Star Trek represents All of Church History |

|

The Star Trek series and films retell this through its humans, aliens, and technology. It displays Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy and sometimes even offshoots like Gnosticism, Islam, and Protestantism. Let us boldly go where no historian has gone before ....

|

Note: When I say "Star Trek," I'm talking about the five complete television series and the first ten movies that canonically comprise it. I'm not going to include the latest three "reboot" films and the currently running Star Trek: Discovery series (though I may deal with them eventually) or the hundreds of novels, fan fiction film projects, and who knows what else. Also, if you haven't seen Star Trek, here is An Episode & Movie Guide.

|

| | IS STAR TREK ANTI-RELIGIOUS? | |

First of all, Star Trek often brings to mind "secular humanism," an atheistic/agnostic philosophy that rejects religion in favor of "reason/science." It is said its characters are "irreligious" and its depiction of religion as a whole rather "negative." After all, Gene Roddenberry, the most worshipped of the show's creators, openly promoted a "secular humanist philosophy."

"Secular humanism," despite originating from the west, condemns a major component of western civilization, namely, the Church. Sometimes, it seems secular humanism is an unintended byproduct of the Church, much to the chagrin of both parties. Nonetheless, secular humanists cannot help but be molded by the Church's pervasive historical influence, nor can Star Trek. Michael Jindra, research scholar at Notre Dame University, contributing to the collection of essays titled Star Trek and Sacred Ground: Explorations of Star Trek, Religion, and American Culture has noted the plentiful western (and, thus by extension, Christian) themes in the series:

MICHAEL JINDRA: RESEARCH SCHOLAR AT NOTRE DAME UNIVERSITY

"Star Trek has succeeded as an ongoing narrative and become one of the largest cultural phenomenons of this century because it has an overarching philosophy that draws on central themes of the Western tradition. It appeals to fans brought up in that tradition, most of whom are found in Europe and North America. For many, Star Trek has taken a place alongside the traditional metanarratives and mythologies of Western cultures, largely because it draws on them and portrays humanist, scientific, and Christian themes in the very vivid and attractive media of television and film."

|

|

A Star Trek screenwriter, David Gerrold, interestingly stated, "Gene [Roddenberry] was a historical revisionist." Jon Wagner (professor of anthropology at Knox College) and Jan Lundeen (teacher of sociology at Carl Sandburg College) co-wrote Deep Space and Sacred Time: Star Trek in the American Mythos, says something similar:

JON WAGNER & JAN LUNDEEN: ANTHROPOLOGIST & SOCIOLOGIST

"Star Trek was loaded with such recycled narrative artifacts as gangsters, gunfighters, witches, and swashbuckling Samurais-not to mention Biblical phrases, Greco-Roman mythological references, snippets of Shakespeare, and so forth. From the beginning, Trek thus inserted itself into an ancient and ongoing project of 're-visioning' the themes of earlier narratives, a practice that in turn provides material for still more revisionings (parodies, jokes, fan fiction, Trek novels, and even, perhaps, new mythic worlds inspired by Trek).

|

|

Could Star Trek's mission be to display a "superior" version of the West's religious past as an irreligious (if not fanciful) future with symbolic/historical similarities that westerners (even religious ones) will be inclined to appreciate? Is it a "representation" of western history, that is, "re-presenting" everything so that humanism is the saving and guiding force of history instead of God? Regardless of how wishful or conscious, could it be a secular humanist replacement for the Church's history?

Could Star Trek's mission be to display a "superior" version of the West's religious past as an irreligious (if not fanciful) future with symbolic/historical similarities that westerners (even religious ones) will be inclined to appreciate? Is it a "representation" of western history, that is, "re-presenting" everything so that humanism is the saving and guiding force of history instead of God? Regardless of how wishful or conscious, could it be a secular humanist replacement for the Church's history?

If Star Trek is anti-religious, why are its fans so often been mocked as cultists? "Many Star Trek fans," Jindra argues, "though denying that their adherence to Star Trek is religious, still use religious language to express their fandom." Could this be related to how secular humanism is accused of trying to replace religion by effectively becoming another religion? It may not believe in God, but theism isn't definitionally required, as is seen with Scientology, an atheistic religion founded by L. Ron Hubbard. It is suspicious that one of Star Trek's producers, Rick Berman, reported this about Gene Roddenberry: "I remember he used to tell me that L. Ron Hubbard was a friend of his and he went and started a religion. Gene always thought that if he had wanted to he probably could have done the same thing."

MICHAEL JINDRA: RESEARCH SCHOLAR AT NOTRE DAME UNIVERSITY

"Religion is given a sociologically broad and 'functional' definition as a 'symbol system' concerned with 'ultimate' questions about the world, human destiny, and 'transcendent meaning' .... Based upon this definition, it is not hard to argue that Star Trek is religious."

|

|

Some Star Trek episodes and films are "preachy," putting forth ideals about how humanity should act, unavoidably giving it a religious flavor. Many enthusiastically embrace it and end up traveling to Star Trek conventions like pilgrims.

Some Star Trek episodes and films are "preachy," putting forth ideals about how humanity should act, unavoidably giving it a religious flavor. Many enthusiastically embrace it and end up traveling to Star Trek conventions like pilgrims.

If Star Trek is "religious," it is of course not necessarily "Christian." Jeffrey Scott Lamp (who wrote "Biblical Interpretation in the Star Trek Universe: Going Where Some Have Gone Before" in Star Trek and Sacred Ground) argued some Star Trek themes run contrary to Christianity ... yet he also admitted, "The major religious tradition within which the Star Trek universe was conceived and defined is Western Christendom." So, even if Star Trek is a religion unto itself, it is not automatically unrelated to Church history. It might be a kind of Church heresy utilizing historical revisionism for its unorthodox designs.

According to the theology professor at Oxford, Larry Kreitzer, Star Trek has "many important theological declarations from the Judeo-Christian heritage." Star Trek came from the West, which was shaped by Christianity, so it would be difficult for it to shake off the Church's influence, even if it has been trying to do so the whole time. But has it?

Humanity in Star Trek betters themselves through "science" and "reason," but is this at odds with Christian claims that humanity should rely on God? There are "Christian Humanists" (Leonardo da Vinci, Pope John Paul II) that said reliance on God can work alongside our ability to improve ourselves through reason and science, even if fundamentalists, both secular and religious, abhor this idea.

Humanity in Star Trek betters themselves through "science" and "reason," but is this at odds with Christian claims that humanity should rely on God? There are "Christian Humanists" (Leonardo da Vinci, Pope John Paul II) that said reliance on God can work alongside our ability to improve ourselves through reason and science, even if fundamentalists, both secular and religious, abhor this idea.

So, does Star Trek specifically promote "Secular Humanism" or merely an unspecified "humanism" that does not necessarily exclude "Christian Humanism?"

Star Trek here and there shows a need for humans to submit themselves to a higher power. When main characters are determined to overcome some trial all by themselves (as good secular humanists would do), they can end up bending to the will of a god-like force which resolves the problem instead (the episode "Q Who" from The Next Generation is a prime example, but more shall be pointed out). Wagner and Lundeen said this points to the central theme in the whole franchise:

JON WAGNER & JAN LUNDEEN: ANTHROPOLOGIST & SOCIOLOGIST

"Of all the philosophical issues addressed in Star Trek none is more deeply pervasive than the question of humanity's potential for moral self-elevation and, by implication, the need for a deity as humankind's mentor and judge. Trek explores this potentially divisive issue in a way that only myth can do, reframing it on a plane where it appears, however illusively, to lend itself to reconciliation -- and what's more, a reconciliation that valorizes humanism while avoiding an overt confrontation with American's religious sensitivities and even, for some fans and commentators, expressing a serendipitous harmony with Judeo-Christian ideals."

|

|

This would make Star Trek more like "Christian Humanism" than "Secular Humanism," depicting humanity perfecting themselves and having a reliance on God (or some analogous "higher power"). Many find this repugnant to science fiction. However, Michèle Barrett (professor of Modern Literary and Cultural Theory at Queen Mary, University of London) and her son Duncan Barrett (then student at City of London School) wrote the book Star Trek: The Human Frontier, in which they, while insisting faith and reason are incompatible, strangely admit to the surprising compatibility between Star Trek and the supernatural claims of Christianity: "The basic premise of Christian belief, the incarnation of God in a human form, is just the kind of thing that cyborg science fiction is full of."

Star Trek occasionally depicts corrupt alien religions, thus condemning all religion and Christianity by implication ... right? As Wagner and Lundeen point out, "The denunciation of false gods is not in itself antireligious; on the contrary, it appears in the Bible." Lambasting some religions does not amount to rejecting every religion. The Catholic Church has condemned other religions, even to the ironic criticism of secular humanists who praise Star Trek for doing the same thing.

Star Trek occasionally depicts corrupt alien religions, thus condemning all religion and Christianity by implication ... right? As Wagner and Lundeen point out, "The denunciation of false gods is not in itself antireligious; on the contrary, it appears in the Bible." Lambasting some religions does not amount to rejecting every religion. The Catholic Church has condemned other religions, even to the ironic criticism of secular humanists who praise Star Trek for doing the same thing.

However, Star Trek only denies gods and never affirms any ... right? In the episode "Who Mourns for Adonais?" (of The Original Series), Captain Kirk is confronted by an alien life form in the guise of the Greek god Apollo who demands Kirk worship him, to which Kirk responds, "Mankind has no need for gods. We find the 'One' quite adequate." Instead of atheism, Kirk's words merely deny polytheism (belief in many gods) and affirm monotheism (belief in one God). Some say this settles the issue: Star Trek, like Christianity, believes in God.

Could Star Trek, however, still be anti-religious? It comes close with the episode "Who Watches the Watchers" in The Next Generation (as we will see). However, whenever Christianity comes up (and it does come up), it is done with ambivalence or adulation (see the "Bread and Circuses" episode from The Original Series). And, again, the fact that protagonists come up against negatively depicted religions is no proof of it being anti-religious or anti-Christian. Rather, the fact that it does condemn faulty religions while offering praise to Christianity might suggest that Star Trek is simply ... Christian.

If Star Trek is somehow a manifestation of a Catholic/Christian conciousness, my thesis that it corresponds somehow to Church history becomes even more conceivable. It would certainly be a most fantastical rendition of it but possibly not too dissimilar to the magical tales of King Arthur which symbolize the various histories of the Bible.

But is Star Trek really Christian? One last thing should be looked at ...

| | IS STAR TREK ALL OF THE ABOVE? | |

As tempting as it might be to categorize Star Trek as entirely secular, cultish, or Christian, I have found it to be more complicated. Sometimes, it seems wholly indifferent toward both atheism and religion, and other times, it seems to mix the two in a confused and bewildering manner. Both atheists (even the militant variety) and Christians (even the clerical variety) have argued both sides. Wagner and Lundeen point out, "Critical views of Star Trek, then, run the gamut-some praising Trek as deep psychic insight and others denouncing it as oppressive propaganda."

One might look to the creators of Star Trek to understand its inconsistent treatment of religion. Gene Roddenberry, although reported to be an atheist, held views on religion that were all over the place, sometimes not even indicating atheism. Moreover, the show technically had multiple creators.

GREGORY PETERSON: PROFESSOR OF RELIGION AT THIEL COLLEGE

"One option is to assume that these apparent contradictions [in Star Trek] are the typical result of composite authorship which bedevils any television series, where screenwriters, directors, producers, and network executives all can and do contribute to forming a final product."

|

|

While Roddenberry took the lion's share of the credit, his involvement in the series is legendarily exaggerated, especially considering he has been dead for the vast majority of Star Trek's episodes and films. Many others shaped the franchise both during and after his life, and consequently, a plethora of contradictions have slipped past continuity inspection, including those of ideological nature.

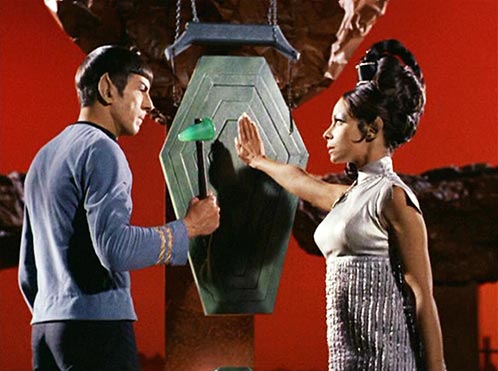

If one example could be highlighted up front regarding the show's ambiguity toward religion, one might again consider how it doesn't reveal any significant presence of religiosity among its main characters. Technically, however, as we will see, there are main characters who are most definitely religious (e.g. Spock, Worf, Quark, Kira, Sisko, Chakotay, Torres), yet all of them subscribe to various fictional belief systems. Does this mean anything? Is it meant to suggest that all humans in the future will "grow out" of the earth-originated faiths? Or is it fallacious to conclude that just because we don't see a certain character practicing a real religion means that they must not be practicing anything at all?

If one example could be highlighted up front regarding the show's ambiguity toward religion, one might again consider how it doesn't reveal any significant presence of religiosity among its main characters. Technically, however, as we will see, there are main characters who are most definitely religious (e.g. Spock, Worf, Quark, Kira, Sisko, Chakotay, Torres), yet all of them subscribe to various fictional belief systems. Does this mean anything? Is it meant to suggest that all humans in the future will "grow out" of the earth-originated faiths? Or is it fallacious to conclude that just because we don't see a certain character practicing a real religion means that they must not be practicing anything at all?

Again, it is never made clear that Christianity or other existing faiths have stopped existing. There is mention that the Catholic Mass is still being celebrated in St. Peter's basilica during Star Trek: Enterprise, implying that the Catholic Church at least continues to endure. We also know that the starship Enterprise of The Original Series has a "chapel" presumably for earth-based religious services (since we see only humans using it, not to mention that the crew is nearly all human). Still, most of the characters are not seen professing any faith. Roddenberry did criticize religion but also claimed that, in the future, religion will not disappear but simply become more private. Is it so private in Star Trek that the camera does not capture it most of the time? Or, perhaps, as others argue, is its conspicuous invisibility due to the producers' desire to avoid potential controversy which might arise if any real religion entered the picture?

JON WAGNER & JAN LUNDEEN: ANTHROPOLOGIST & SOCIOLOGIST

"Although Gene Roddenberry was known for his outspoken criticism of organized religion, Star Trek's narrative approach cannot simply be dismissed as an allegorical diatribe against America's religious beliefs. Whatever Roddenberry's views on religion (and his views were actually rather complex), the Trek series and films, as they became canonized in our popular culture, are striking not so much for their expression of any particular pro- or anti religious dogma as for their ability to construct a humanist mythos without contradicting the religious beliefs espoused by the majority of Americans."

|

|

In conclusion, I contend that Star Trek, taken as one seamless whole, cannot definitively be interpreted as a pure work of secular philosophy nor of Catholic theology. Rather, elements of both seem to be present in it. Maybe you could say it's meant to reflect the modern world, which also currently exists as a confusing mixture of both Christian and atheistic thinking. Perhaps Star Trek is an attempt to sort this out.

The main thesis here is that Star Trek is Church history, whether in homage to it, some kind of "evil twin," or a suspicious conjunction of the two.

The Catholic historian Christopher Dawson said, "It is impossible to understand Christianity without studying the history of Christianity." Hopefully, my work will show this. If you are already satisfied with your knowledge about Church history, I would still say there's significant value in seeing it dressed up in mythical clothing.

JON WAGNER & JAN LUNDEEN: ANTHROPOLOGIST & SOCIOLOGIST

"Although Euro-Americans often view themselves as a predominantly rational and practical people, we too live in a world held together by narratives. Some of our narratives are consciously recognized as stories and told as such, while others have a more subliminal but no less profound presence."

|

|

The mythical setting here is, of course, Star Trek. Even if you are unfamiliar with it, you still might be able to follow along. On the other hand, you might want to just watch it (here is An Episode & Movie Guide). Star Trek is a highly influential and enduring cultural phenomenon and, as I shall show, an interesting example of how Christianity has fixed itself upon the western imagination, even among those who are trying to get rid of it. The franchise has an interesting view of the future and has inspired many people throughout the world to shape our future accordingly. On the other hand, this vision of the future is a vision of the past.

|

|

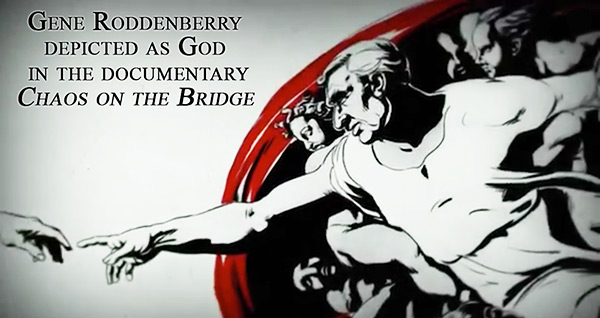

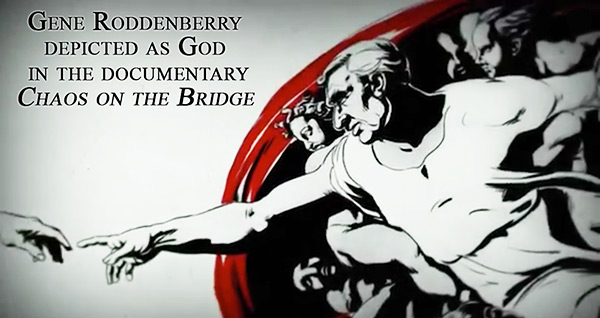

Roddenberry is "God" in Star Trek, an unseen being in the story and its ultimate creator. Many fans judge the success and failure of each character, writer, or series based on its conformity with his stated will. Even after his death in 1991, many believe the show followed his great plan like divine providence. Others became skeptical, not keeping the faith. Michael Jindra states, "Some fans take Gene Roddeberry's word as absolute, and his vision of Star Trek and the world as the 'correct' one, a view often expressed in debates over the Star Trek 'canon'" and "Among these fans, the folk philosophy of Star Trek begins to show the attributes of an institutionalized religion."

Did Roddenberry mean to set himself up as God? While raised Christian (as many secular humanists are), he became an atheist and then waffled on it a bit. When asked about God, Roddenberry answered how he used to hold "ordinary" views but then said, "As nearly as I can concentrate on the question today, I believe I am God."

J.R.R. Tolkien (Catholic writer of The Lord of the Rings) said God is the ultimate Creator but each human is a "sub-creator" when making art, reflecting, however faint, God Himself. This would hold true even for atheists.

Gene Roddenberry was scandalously imperfect, ironically seeing himself too much like a god and consequently acting beyond morality. As Joel Engel laid out in Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man behind Star Trek, Roddenberry was a serial adulterer, a prolific drug user, and arguably got away with a bit of manslaughter. Many fans reinforced the image of Roddenberry as "sole creator," rather than acknowledging the pantheon of creators, as if to insist the mythos of Star Trek must indeed possess a monotheistic quality. In this way, Roddenberry symbolically has more in common with the Christian God than a typical polytheistic deity, and many seem to want to preserve that feeling often by ignoring Roddenberry's libertine lifestyle which would suggest something more like the pagan god Zeus. Incidentally, this behavior also reinforces the stereotype of Star Trek being a cult, as cultists often overlook the transgressions of their leader, especially when he sets himself up as divine. Gene Roddenberry was scandalously imperfect, ironically seeing himself too much like a god and consequently acting beyond morality. As Joel Engel laid out in Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man behind Star Trek, Roddenberry was a serial adulterer, a prolific drug user, and arguably got away with a bit of manslaughter. Many fans reinforced the image of Roddenberry as "sole creator," rather than acknowledging the pantheon of creators, as if to insist the mythos of Star Trek must indeed possess a monotheistic quality. In this way, Roddenberry symbolically has more in common with the Christian God than a typical polytheistic deity, and many seem to want to preserve that feeling often by ignoring Roddenberry's libertine lifestyle which would suggest something more like the pagan god Zeus. Incidentally, this behavior also reinforces the stereotype of Star Trek being a cult, as cultists often overlook the transgressions of their leader, especially when he sets himself up as divine.

Even with this harsh criticism of Gene Roddenberry, I do not pour equal criticism upon Star Trek. His influence has been exaggerated, and one need not slavishly interpret the show in terms of his professed (and mixed) worldview. It is still nonetheless part of the larger Star Trek epic that a man named Gene Roddenberry is mythologically an omnipresent force throughout its cosmos. That's how the story has effectively come to be told, both by its fans and many of its producers, and it has subtly impacted the show's writing. Gene Roddenberry is "The Great Bird of the Galaxy," as his curious epithet goes (a divine-sounding name, reminiscent of the heavenly dove that symbolizes the Holy Spirit). It's not that it's ... true. It's just part of the legend at this point. And the legend is what I'm talking about, a story which, as I will show, despite its multitudinous shortcomings, shows itself constructed from the building blocks of the Church's past.

|

|

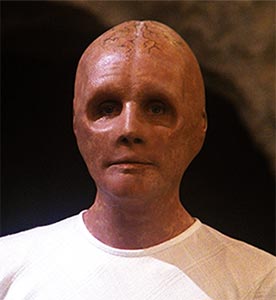

ZEFRAM COCHRANE

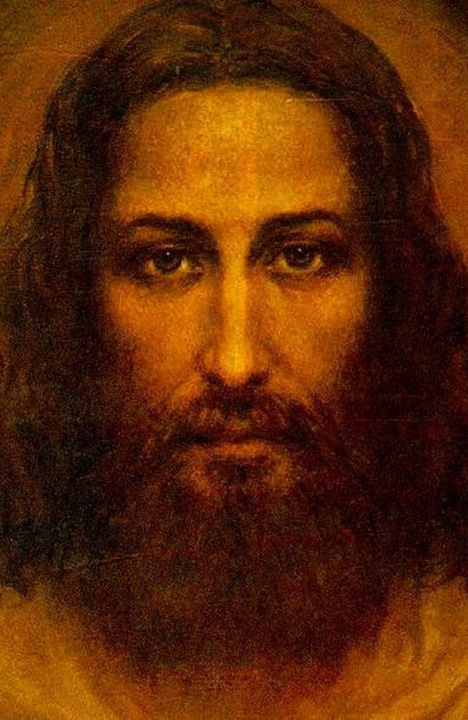

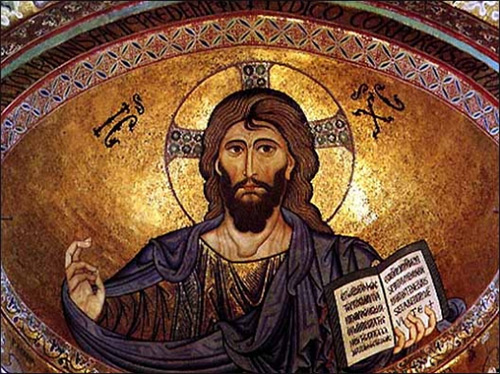

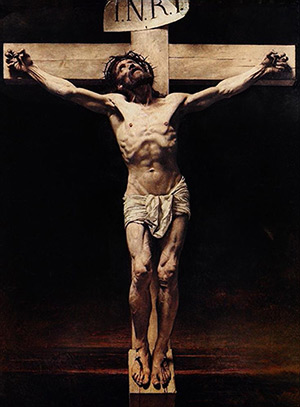

JESUS CHRIST

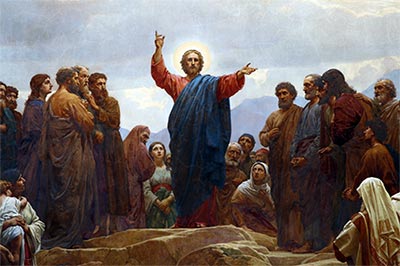

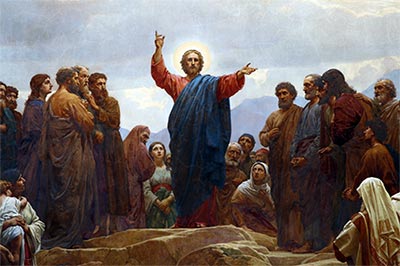

Mentions of his name and appearences are few, but he is the most important character in Star Trek. He is the man who invents earth's "Warp Drive," the technology that allows mankind to travel faster than the speed of light, allowing access to the stars, thus providing the basis for all of Star Trek. Cochrane's work sparked a kind of salvation to a broken earth by launching humanity toward a final frontier. It gave humans a renewed sense of purpose to seek out "new life" and "new civilizations." The character of William Riker, when asked to identify the most important example of progress in the recent centuries, unhesitatingly answers, "I suppose the warp coil. Before there was warp drive, humans were confined to a single sector of the galaxy." Spock even tells us, "The name of Zefram Cochrane is revered throughout the known galaxy. Planets were named after him. Great universities, cities." Zefram Cochrane is a savior of the human race. He is Star Trek's Jesus.

Cochrane and Christ gave humanity access to "the heavens," sparked transformation in the world, and became examples which mankind would aspire to. They both were unlikely heroes from lowly backgrounds, one a humble carpenter from the backwater village of Bethlehem, the other a struggling engineer in the Montana backcountry of Bozeman. But the stars would shine upon them. Travellers from distant reaches would pay them respect.

A serious objection could be raised against this interpretation. As we see in Star Trek: First Contact (which was made after Roddenberry's death), Zefram Cochrane is extremely worldly, money-loving, sex-obsessed drunkard, very much in contrast to the example of Christ. He doesn't undertake his warp flight out of some selfless, idealistic desire to better humanity but rather out of a desire to get rich. Interestingly, this also seems to pose a problem for the message of Star Trek itself. Brannon Braga, one of the major Star Trek producers, commented on this, saying, "We thought it would be cool if the man who basically ushered in a new era of humanity was motivated by things that were antithetical to Star Trek." Ronald D. Moore, another major producer, likewise had said, "Let's get simple. Bring Cochrane into the story. Let's make him an interesting fellow, and it could say something about the birth of the Federation. The future that Gene Roddenberry envisioned is born out of this very flawed man, who is not larger than life but an ordinary flawed human being." A serious objection could be raised against this interpretation. As we see in Star Trek: First Contact (which was made after Roddenberry's death), Zefram Cochrane is extremely worldly, money-loving, sex-obsessed drunkard, very much in contrast to the example of Christ. He doesn't undertake his warp flight out of some selfless, idealistic desire to better humanity but rather out of a desire to get rich. Interestingly, this also seems to pose a problem for the message of Star Trek itself. Brannon Braga, one of the major Star Trek producers, commented on this, saying, "We thought it would be cool if the man who basically ushered in a new era of humanity was motivated by things that were antithetical to Star Trek." Ronald D. Moore, another major producer, likewise had said, "Let's get simple. Bring Cochrane into the story. Let's make him an interesting fellow, and it could say something about the birth of the Federation. The future that Gene Roddenberry envisioned is born out of this very flawed man, who is not larger than life but an ordinary flawed human being."

Why would the producers depict Zefram Cochrane with so many flaws? What was their conscious (or unconcious) motive? It turns out, that both Braga and Moore admitted that when they finished flushing out this soiled dimension of Cochrane's character, they realized that they had made him "a Roddenberry person." Anthony Pascale, a news editor who contributed to the DVD audio commentary of First Contact, also got this impression, explaining, "I always felt that the way they treated Cochrane is kind of like Roddenberry. Roddenberry's revered as this god-like visionary, but Gene Roddenberry was a human being with flaws, you know, but that doesn't mean he isn't also a great man and a great visionary." This is extremely important because the flaws portrayed in Zefram Cochrane, while admittedly differentiating him from Christ, nonetheless unites him with Gene Roddenberry, making him, as it were, the creator entering into his own creation, solidifying this unlikely similarity with Christ, who is God made flesh.

It might be mentioned, too, that Cochrane off-handly uses the term "Star Trek" on screen, becoming the only character throughout the whole franchise to speak the title of the show as if he transcends the confines of the fictional universe and possesses some special connection to the real world, the dimension where Roddenberry dwelt.

By design, Zefram Cochrane is without doubt the incarnation of Gene Roddenberry.

In the B.C. era ("Before Cochrane"), the earth is "fallen." When characters time-travel back to it, they are apalled by its igorance and savagery. It is Old Testament times, mankind universally lost in sin without access to the "true way."

In the B.C. era ("Before Cochrane"), the earth is "fallen." When characters time-travel back to it, they are apalled by its igorance and savagery. It is Old Testament times, mankind universally lost in sin without access to the "true way."

The warp-capable vessel Cochrane builds is the Phoenix, named after the mythological bird that bursts into flames at the end of its life, only to be reborn again in its ashes, relating to this dying earth scorched by nuclear warfare yet brought to new life by this monumental flight. Wagner and Lundeen put it: "At that moment, Cochrane's ship, the Phoenix, is rising from the ashes of its ruined world." The Phoenix's connection to death and resurrection has naturally been a symbol for Christ early on, whose death and resurrection is the means by which the world was spiritually saved from eternal death. Cochrane's vessel is fittingly made from a nuclear missile meant for destruction but repurposed for something more uplifting. Christ's instrument of salvation was a deathly instrument, namely a cross, crucifixion being a most excruciating form of execution at the time. One might even consider a theological connection to the first nuclear bomb test (of the Manhattan Project), which was curiously dubbed "The Trinity Test" ... though I'll leave others to ponder that one.

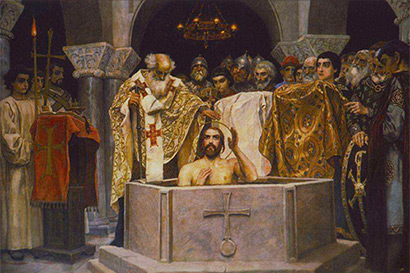

Fascinatingly, while Cochrane's warp flight took place in 2063, he was born in 2030 (despite looking much older, theoretically due to radiation poisoning), making Cochrane 33 years old at the time, the traditional age Christ was when he was crucified.

Both Zefram Cochrane and Jesus Christ ultimately ascended and vanished from the face of the earth. Scripture tells how, after his resurrection, Jesus remained on earth for a time to teach his disciples a few last things before his "Ascension into Heaven," after which he was never seen again (except to a privileged few). Likewise, we are told that Zefram Cochrane, after accomplishing his work and imparting wisdom to the new generation he inspired, eventually took flight into space once more ... and mysteriously disappeared. Like Christ, it was reported that Cochrane's body was never found.

Both Zefram Cochrane and Jesus Christ ultimately ascended and vanished from the face of the earth. Scripture tells how, after his resurrection, Jesus remained on earth for a time to teach his disciples a few last things before his "Ascension into Heaven," after which he was never seen again (except to a privileged few). Likewise, we are told that Zefram Cochrane, after accomplishing his work and imparting wisdom to the new generation he inspired, eventually took flight into space once more ... and mysteriously disappeared. Like Christ, it was reported that Cochrane's body was never found.

Cochrane's story gets even stranger with The Original Series episode "Metamorphosis," when several decades later, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy stumble upon a Zefram Cochrane who is alive and well. They learn that Cochrane in his last journey was nearly dead but was rejuvenated by a spiritual-like entity called "The Companion" which bestows everlasting life. It develops a special relationship with Cochrane and periodically envelops him, preserving his health and undoing the mortal effects of age. Spock describes it as "almost a symbiosis of some kind, a sort of joining," while Kirk says it's "like love." While being suspicious of it at first, they ultimately realize that it is truly beneficient being. The episode concludes with the Companion integrating itself into a willing human woman and becoming not only a spiritual but physical lover of Cochrane. It is quite an odd episode, but the Christ-like imagery is inescapable. Not only did Cochrane gain a "glorified" and immortal body like Christ, he is accompanied by a supernatural-like force that bears a curious resemblence to the Holy Spirit, a union which Cochrane says is "hard to explain" (not unlike the ineffable relations between the persons of the Trinity). Both the Companion and the Holy Spirit have a connection to love itself and give life to those it possesses (one physical and the other spiritual). Betsy Caprio (author of Star Trek: Good News in Modern Images) notes, "Pure consciousness -- here in the form of the mysterious female Companion -- is a good symbol of God." Those who are filled with the Holy Spirit become "lovers" of Christ, which is what we see reflected when the Companion joins with the willing female who then becomes the lover of Cochrane. These are strange but defining events for the character of Cochrane, as the episode in question was technically the first appearance of the character on screen. It seems even Gene Roddenberry originally designed this character to have both a worldly and almost otherworldly significance ... that is, both human and divine.

|

|

The "humanism" in Star Trek gives the human race a religious significance.

Prior to Zefram Cochrane, humanity was "inhumane," comparable to Old Testament times, that is, proto-Christian at best. With Cochrane, humanity blossoms, like God had promised Abraham about how his descendents would spread throughout the nations and become as numerous as the stars.

In Star Trek, humans deeply respect "The Great Books" (e.g. Charles Dickens, Moby Dick, and William Shakespeare), as they express humanist ideas, despite their pre-Cochrane authorship, mimicing how Christians respect "The Good Book," especially the Old Testament in this case, both having "prepared the way" and still worthy of study in the present. They have something like a New Testament as well, which tell about Christ specifically, or, in this case, Cochrane. Characters look back on him, both in his words and deeds, as a guiding light. Cochrane's quote, "Don't try to be a great man. Just be a man, and let history make its own judgments," has a humble and Christ-like ring to it, and he would coin the famous phrases that would define humanity's new purpose, that is, exploring "strange new worlds," seeking out "new life and new civilizations," and going boldly "where no man has gone before."

While humanist literature is the sacred scripture of Star Trek, humanist science is the theology (known as "The Divine Science," traditionally). Characters in Star Trek pour over the complexities of scientific systems like monks over the minutiae of theological treatises. Each utilizes their science to solve problems, whether a crisis in engineering or a crisis in Church teaching. Both have a ponderous use of "technobabble," much of it a mystery to the layman, yet it is a meaningful extension of both Star Trek and the Church.

Nevertheless, "physical science" and "divine science" have two different subject matters. The typical science of humanists (and of Star Trek) studies the material universe, while theology studies the supreme being who exists immaterially and independently of the universe. Vast amounts of ink have been spilt over maintaining the distinction between these two fields, oftentimes with the goal of isolating and annihilating one of them. From a traditional Catholic perspective, the two are not so divorced. Not only is man the image of God, but all creation to some extent is the image of the Creator. When you study a masterpiece, you learn something of the Master. Nature itself may not be divine, but it resembles it, however faintly. It is the reason why medieval monks of western Europe studied it as an extension of their religious faith, and why this led to discoveries which slowly evolved into what became modern science. This general attitude survives among unbelieving scientists, though often they go further, effectively treating the universe not as a mere divine reflection but as a divine reality itself ... as God Himself. This is "pantheism," the belief that God and the universe are the same thing, and it's curiously something that various atheists freely admit to, viewing it as a poetic way to think about the world and regard it higher than anything else (a sort of "sexed-up atheism" as the atheist Richard Dawkins put it). Despite any anti-religious motives, secular scientists retain an admittedly quasi-religious mindset in their work, approaching nature somewhat like how a Catholic would approach the divine nature.

Nevertheless, "physical science" and "divine science" have two different subject matters. The typical science of humanists (and of Star Trek) studies the material universe, while theology studies the supreme being who exists immaterially and independently of the universe. Vast amounts of ink have been spilt over maintaining the distinction between these two fields, oftentimes with the goal of isolating and annihilating one of them. From a traditional Catholic perspective, the two are not so divorced. Not only is man the image of God, but all creation to some extent is the image of the Creator. When you study a masterpiece, you learn something of the Master. Nature itself may not be divine, but it resembles it, however faintly. It is the reason why medieval monks of western Europe studied it as an extension of their religious faith, and why this led to discoveries which slowly evolved into what became modern science. This general attitude survives among unbelieving scientists, though often they go further, effectively treating the universe not as a mere divine reflection but as a divine reality itself ... as God Himself. This is "pantheism," the belief that God and the universe are the same thing, and it's curiously something that various atheists freely admit to, viewing it as a poetic way to think about the world and regard it higher than anything else (a sort of "sexed-up atheism" as the atheist Richard Dawkins put it). Despite any anti-religious motives, secular scientists retain an admittedly quasi-religious mindset in their work, approaching nature somewhat like how a Catholic would approach the divine nature.

The hallowed portrayal of science throughout Star Trek can variously be interpreted to reflect either the "theistic theology" of Christianity or the poetic "pantheistic theology" associated with secular scientists (one famously being Albert Einstein). Star Trek doesn't definitively fall on one side or the other, again probably to avoid displeasing either side of their divided fanbase, yet Star Trek's science bears symbolic theological significance descended in one way or another from the Catholic tradition. It should soften the suspicion regarding the supposedly mutually exclusive differences between science and religion and thus open the mind up to consider avenues of mutual respect. The book The Gospel According to Science Fiction, Gabriel McKee makes the interesting case:

GABRIEL McKEE: THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO SCIENCE FICTION

"... religion is as much a quest for knowledge as is science, and science cares as much about the unseen and the unproven as does religious faith. Far from being merely 'non overlapping magisterial' with nothing to do with one another, science and religious experience can in fact strengthen one another. In faith, the scientist can find a driving factor for exploration, a divine reason to inquire into the world's mysteries. In science, the believer can uncover the secrets of God's majesty, perhaps finding in subatomic particles or distant stars something mystical. SF [science fiction] explores futuristic approaches to belief and transcendence, and in that realm it finds the rich common ground between these two often-opposed methods of understanding."

|

|

Star Trek often focuses on emotion, despite celebrating reason. It adulates humanity, which has logic and feelings, thus rejecting logic as the only ingredient to well-being. As Thomas Richards (author of The Meaning of Star Trek) puts it, "The series constantly reminds us that technical rationality has its limits." Believing precise science can fix all problems is like believing precise theology can fix all problems, but mere knowledge is not enough. Theology and science can screw things up in the hands of the wrong people. Doctrine, of course, is a component to a Christian, but there is a fluid (and troublesome) side more "spiritual" or "mystical." Human emotion, in part, symbolizes this in Star Trek.

Star Trek often focuses on emotion, despite celebrating reason. It adulates humanity, which has logic and feelings, thus rejecting logic as the only ingredient to well-being. As Thomas Richards (author of The Meaning of Star Trek) puts it, "The series constantly reminds us that technical rationality has its limits." Believing precise science can fix all problems is like believing precise theology can fix all problems, but mere knowledge is not enough. Theology and science can screw things up in the hands of the wrong people. Doctrine, of course, is a component to a Christian, but there is a fluid (and troublesome) side more "spiritual" or "mystical." Human emotion, in part, symbolizes this in Star Trek.

There is "the dark night of the soul" in the spiritual life, dark emotional moments that characters in Star Trek are periodically forced to endure. We see the show's various flawed characters gaining personal growth through such experiences, yet we also see its many characters who are without any noticeable flaws having to endure such experiences as well. The various so-called "perfect" (or "nearly perfect") characters could be called "secular saints," and therefore a reflection of actual saints. In both cases, such paragons are confronted with spiritual darkness, where their near-perfect selves are ripped apart and put back together, sometimes not so much for the benefit of themselves but for others, reflecting the very Catholic notion that saints (and ultimately Christ) are given forms of suffering which ultimately aid others. Such emotional and spiritual tribulation can even take the form of apparent conflicts pertaining to established science (or, likewise, established theology). Certainly Christians struggle when their spiritual trials seem irreconciliable with their known theology, just as Star Trek's characters struggle when their emotional trials seem irreconciliable with their known science, something which may need to expansion if they wish to be victorious.

Humanism is "anthropocentric" ("human-centered"), insofar as humans are seen as supremely significant. Despite the plethora of non-human life forms, one gets the impression that humans are special in Star Trek, not so much in physical abilities but in their culture and morality. Star Trek centers around humanity and thus it is "anthropocentric." In contrast, we have the term "Christocentric," a theological term that "Christ" or "Christianity" is of supreme importance. Historically, Renaissance and Modern Philosophy shifted from a "Christocentric" to an "anthropocentric" view of things, a movement interpretated as replacing "God" (Christ) with "Man." This is what Secular Humanism does, creating a perceived hostility between the two.

Ironically, some accuse Christocentrism as being anthropocentric, implying humans have a privileged position in the cosmos above other life forms through having the distinction of having God incarnate into their race. This "anthropocentrism" helped hammer in the belief that earth, the home of humanity, was the center of the universe. But even if earth is just a "spiritual center" and not a "physical center," Star Trek's recognizable anthropocentrism would not necessarily be at odds with a Christocentric understanding of the universe. Postmodern anti-humanists have criticized Star Trek as they have the Church, calling it "racist" in its depiction of humanity's superior righteousness over other races, as they have criticized Christianity considering itself superior to all other religions.

Even if Star Trek is anthropocentric, is it Christocentric? Obviously, not explicitly so. There are Christ figures in stories throughout history that do not mention "Christ," "Christianity," "religion," or even "God," but this does not prohibit them from being useful in thinking about those very things. "Humanity" is the "main character" and the "hero" of Star Trek, a sort of "Christ figure," or collectively in all its Christ figures, a sort of "Christianity figure." This works even if viewing it as atheistic, as Michèle Barrett and Duncan Barrett did, "In some way the ethos of Star Trek is comparable to the beliefs of Ludwig Feuerbach, who argued that humans should take their place at the moral centre, rather than projecting all that was good on to an outside being (that is, God) and internalizing all that was bad as 'sin'." Feuerbach's philosophy, you see, was that our concept of God was merely a psychological way to express what was really true about us and that Christianity was actually a step in our evolution towards this realization, that supposedly the idea of the Incarnation was not really God becoming man but us subtly realizing that man is God. If Christianity is really just a psychological projection of an atheistic reality about our own human greatness, the supposedly atheistic vision of Star Trek could find all the more suprisingly common ground with what Feuerbach claimed to see unfolding in the history of the Church.

Even if Star Trek is anthropocentric, is it Christocentric? Obviously, not explicitly so. There are Christ figures in stories throughout history that do not mention "Christ," "Christianity," "religion," or even "God," but this does not prohibit them from being useful in thinking about those very things. "Humanity" is the "main character" and the "hero" of Star Trek, a sort of "Christ figure," or collectively in all its Christ figures, a sort of "Christianity figure." This works even if viewing it as atheistic, as Michèle Barrett and Duncan Barrett did, "In some way the ethos of Star Trek is comparable to the beliefs of Ludwig Feuerbach, who argued that humans should take their place at the moral centre, rather than projecting all that was good on to an outside being (that is, God) and internalizing all that was bad as 'sin'." Feuerbach's philosophy, you see, was that our concept of God was merely a psychological way to express what was really true about us and that Christianity was actually a step in our evolution towards this realization, that supposedly the idea of the Incarnation was not really God becoming man but us subtly realizing that man is God. If Christianity is really just a psychological projection of an atheistic reality about our own human greatness, the supposedly atheistic vision of Star Trek could find all the more suprisingly common ground with what Feuerbach claimed to see unfolding in the history of the Church.

And yet I stress again that despite the show's moments of apparently anti-religious sentiment, there are too many exceptions where the show, sometimes begrudingly, gives way to the acknowledgement of a higher power and consequently admits that humanity itself, despite its resemblence, is ultimately not God. But whether one views Star Trek's intention to get Humanity to act like Christianity, Humanism to act like Catholicism, Anthropocentrism to act like Christocentrism for the purpose of supplanting or honoring the Church, Star Trek being a reflection of Church history strangely works either way.

|

|

|

Humans are Christians and aliens are pagans. "Pagan" often means one not following Abrahamic religion (Christianity, Judaism, or Islam) or at least believing something not having an Abrahamic origin but has now been adopted into an Abrahamic tradition in some way or another (admittedly, broad). Christians have sometimes used it more narrowly to include all non-Christians or even certain Christians whom they doctrinally disagree with (in other words, those deemed to be "heretics"). There is also the more inclusive use of the term that refers to anything that can be known through our natural reason without the aid of divine revelation (such as basic truths about justice). Any given alien race in Star Trek may embody some or all of these meanings of the word "pagan." As you will see, it depends on the alien race.

Both aliens and pagans are often seen as lacking something. This can change, however. In Church History, we see pagans becoming "Christianized pagans." In Star Trek, we see aliens becoming "humanized aliens."

Despite being alien, alien cultures in Star Trek are, of course, human cultures. "The Vulcans, the Romulans, the Klingons, the Cardassians, and the Bajorans all have their own complex and ancient histories-which are often clearly modeled on human historical cultures," says Nancy R. Reagin in the book Star Trek and History. "Space is never completely alien," Alice L. George writes. Even with no clear cultural correlative, an alien race can be something more abstract but still a concern to how humans relate to something "other."

JON WAGNER & JAN LUNDEEN: ANTHROPOLOGIST & SOCIOLOGIST

"If they do have a common feature, it is that they always are us, but only in specific, variable ways. Trek's strategy for employing aliens to define humanity is to hold certain familiar human traits, resulting in a sort of 'controlled thought experiment' that helps us examine and problematize a particular facet of the human condition."

|

|

Moreover, Richards held that the civilizations in the show tend not only to be western but European, which is expected if Star Trek is the history of the western Church especially, as that would be the center of Catholicism, even when sharing the continent with pagan neighbors who have lived there for an even longer period of time:

THOMAS RICHARDS: AUTHOR OF THE MEANING OF STAR TREK

"In Star Trek the galaxy seems to have as many dead civilizations as live ones. In some ways the galaxy in Star Trek is much more like Europe, a place of many dead and vanished cultures, than like America, where large-scale human activity is a more recent phenomenon. Despite the injunction of the series 'to boldly go where no one has gone before,' most of space is full of cultures that have been there before."

|

|

Of course, another reason to consider the obvious connection between humans and Star Trek's aliens is their uncanny physical resemblence to each other. Wagner and Lundeen note how "the Enterprise crew members so routinely encounter human look-alikes in other star systems that they seldom find the fact worthy of comment." However, it is brought up at least a few times, as when Dr. McCoy admits, "I've always wondered why there were so many humanoids scattered through the galaxy." In fact, in a Next Generation episode called "The Chase," it's discovered that all humanoid races have a common genetic ancestry, thanks to an advanced, ancient "Ur-Humanoid" species that spread their DNA throughout the entire galaxy, giving Star Trek's mythology a sort of "Adam and Eve" motif. Kirk even drops the line, "Everyone is human" at one point, something not symbolically meaning "Everyone is Christian" in this case, but rather that all humanoids are literally human on a basic level ... all are "rational animals," as Aristotle would put it, and thus made "in the image of God," as Scripture would put it, and, in that sense, all are at least have the potential of becoming Christian.

Of course, another reason to consider the obvious connection between humans and Star Trek's aliens is their uncanny physical resemblence to each other. Wagner and Lundeen note how "the Enterprise crew members so routinely encounter human look-alikes in other star systems that they seldom find the fact worthy of comment." However, it is brought up at least a few times, as when Dr. McCoy admits, "I've always wondered why there were so many humanoids scattered through the galaxy." In fact, in a Next Generation episode called "The Chase," it's discovered that all humanoid races have a common genetic ancestry, thanks to an advanced, ancient "Ur-Humanoid" species that spread their DNA throughout the entire galaxy, giving Star Trek's mythology a sort of "Adam and Eve" motif. Kirk even drops the line, "Everyone is human" at one point, something not symbolically meaning "Everyone is Christian" in this case, but rather that all humanoids are literally human on a basic level ... all are "rational animals," as Aristotle would put it, and thus made "in the image of God," as Scripture would put it, and, in that sense, all are at least have the potential of becoming Christian.

Now there are exceptions to the rule about aliens representing pagans in Star Trek, especially when it comes to the stranger, non-humanoid flavors. I would say that when the show depicts "non-corporeal life forms," for example, it can often correlate not to pagans but to "spiritual beings," that is, angels, including both the holy and demonic varieties. There are even some instances where an alien being is so god-like that it takes considerable mental effort not to see how it simply symbolizes God. The inclusion of such beings should give one pause, especially for those adamant to interpretating the show as atheistic.

As we said before, humanity's ascent to the stars represents humanity becoming more divine and, specifically in a Christian way, entering into the new life of divine grace. Admittedly, many alien races in Star Trek have also attained space travel as well, and so in some sense, they too have symbolically attained something like that. But while this journey to the stars was profoundly transformative in the case of humanity, we get the sense that it was not always so with other races in the galaxy. Even when humanity finds an alien civilization far superior to that of Earth in some respect (like in technology), they usually are revealed to have some damnable flaw, and even if no flaws are explicitly shown, there is still an overriding sense, gleamed from the show overall, that those aliens still have something lacking, something crucial that is only found among humans. This is not to say that each alien race does not have their own unique strengths, and the same can be said of pagans, even pagan religions, as the Church would admit. In fact, the Catholic Church sees religion in general, even non-Christian ones, as a natural expression of man's desire to be united with the divine, however misguided it can sometimes be. All religions have some truth in them, some more than others, and especially good pagan religions have helped foster natural virtues that make them more recipient to the Gospel. There is even the sense in parts of Catholic tradition that pagans have been prepared by God in a way similar to how God prepared the Hebrew people. St. Clement of Alexandria of the early Church held this view, having said it about the pagan Greeks with regard to their philosophical accomplishments:

CLEMENT OF ALEXANDRIA: EARLY CHURCH FATHER

"Philosophy has been given to the Greeks as their own kind of Covenant, their foundation for the philosophy of Christ ... the philosophy of the Greeks ... contains the basic elements of that genuine and perfect knowledge which is higher than human ... even upon those spiritual objects."

|

|

Even though the Church acknowledges that God can speak to pagans, analagous to how Star Trek's aliens can achieve a divine-like ascent to the stars, things are, once again, not perfect in either case. Not only are aliens consistently portrayed as deficient compared to humanity (especially in the moral sphere), they can often be portrayed as outright demonic. It is consistently suggested that such aliens, if there is any hope for them, can only be saved by humanity. This does not always mean that humans (or Christians) always deal with such cultures in a tolerant manner, but I don't think this is necessarily a criticism. As said before, we see both the humans in Star Trek and the Christians in history practice the art of idol-smashing when such idols have enslaved heathens to an intolerable degree. We also often see many wars spark from such differences, ones that Star Trek almost always depicts as justifiable. Appreciation and tolerance of other cultures is an absolute neither in Star Trek nor certainly in the history of the Church. There is a limit to recognizing the goodness of an alien religion, and no matter how pluralistic Star Trek tries to be, it too inevitably recognizes that. It is, again, why Star Trek has come under criticism for promoting a perceived racism in its elevation of human culture over alien ones, something comparable to how the Church is criticized for naturally elevating Christian religion over those of others.

Even though the Church acknowledges that God can speak to pagans, analagous to how Star Trek's aliens can achieve a divine-like ascent to the stars, things are, once again, not perfect in either case. Not only are aliens consistently portrayed as deficient compared to humanity (especially in the moral sphere), they can often be portrayed as outright demonic. It is consistently suggested that such aliens, if there is any hope for them, can only be saved by humanity. This does not always mean that humans (or Christians) always deal with such cultures in a tolerant manner, but I don't think this is necessarily a criticism. As said before, we see both the humans in Star Trek and the Christians in history practice the art of idol-smashing when such idols have enslaved heathens to an intolerable degree. We also often see many wars spark from such differences, ones that Star Trek almost always depicts as justifiable. Appreciation and tolerance of other cultures is an absolute neither in Star Trek nor certainly in the history of the Church. There is a limit to recognizing the goodness of an alien religion, and no matter how pluralistic Star Trek tries to be, it too inevitably recognizes that. It is, again, why Star Trek has come under criticism for promoting a perceived racism in its elevation of human culture over alien ones, something comparable to how the Church is criticized for naturally elevating Christian religion over those of others.

Of all these things said about paganism, similar things can be said about Islam, Judaism, and heretical branches of Christianity, which again can all fall under "paganism" in the broader sense. The Catholic Church has acknowledged that they all possess degrees of truth in them and thus are not totally lacking a connection with the divine, but it would also say that they lack a fullness in revealed truth.

Even though the aliens in Star Trek represent "pagans," this does not imply they are condemend to remain "merely pagans." Some of them are the equivalent of "Christianized pagans." This symbolically happens when an alien (and perhaps an entire alien race) adopts "human values," or, in other words, becomes a "humanized alien." To be "humanized" is to be "Christianized" in Star Trek. In fact, many examples take the form of humans (or humanized aliens) convincing aliens to be "more merciful" to others and to give up some harsh practice in their culture that they cherish but is spreading misery to everyone. This emphasis on "mercy" strongly reflects the majority of Christ's teachings, famously contrasting the typically unforgiving fixation on mere justice that pagan cultures typically boast of. The aliens who continue to resist adopting human values in Star Trek are invariably depicted as "enemies" and basically "heathens," while those that have given into human values are invariably depicted as "friends" and basically "enlightened." In this way, Star Trek "universalizes" the importance of humanity, making it important not just for itself but for everyone. In fact, you could say that the show makes humanity "catholic," which is the Greek word for "universal." Of course, before Warp drive, humanity did not share their "message" with others, but thanks to Cochrane, and accordingly thanks to Christ, this "message" henceforth spread out to the rest of the world, providing all races with what could even be considered a kind of salvation.

As Michèle and Duncan Barrett say:

MICHÈLE BARRETT & DUNCAN BARRETT: LITERARY CRITICS

"Star Trek is about the human, and endorses a lot of what we might call 'humanist' rhetoric. It frankly favours the human, albeit in an inclusive rather than an exclusive way. It also uses a number of devices to ask questions about how the nature of humanity is to be understood."

|

|

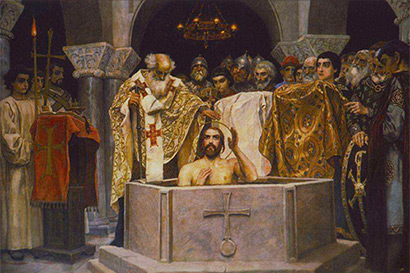

Now, even when an individual or entire people have been baptized, their pagan past inevitably survives to some degree ... sometimes in a problematic way and other times in a harmless or even beneficial way (but most often somewhere in between). Examples where a Christian people's pagan backgrounds led to problems in the Church would include the adoption of torture by medieval European governments thanks to their reverence of ancient pagan Roman law which recommended it, or of the inequalities of the feudal system in Catholic Europe which descended heavily from pagan Viking influence. Examples where a Christian people's pagan backgrounds generally brought relatively harmless or even beneficial qualities could include the Irish Catholic retention of fairy folklore, Scandinavian monks recording the tales of Norse mythology, and certainly Christian Europe's preservation of pagan Greek and Roman philosophy. The Catholic Church has "baptized" many cultures, and more often than not, the baptized culture does not altogether forget their pre-baptized past. This results in a diverse array of cultures that nevertheless profess the same creed (whether it be Christianized Native Americans, Africans, Vietnamese, Arabs, Europeans, etc.). A similar phenomenon is seen in Star Trek, where diverse alien races have come together in communion thanks to humanity, and while they still have their own alien cultures (not to mention their own DNA), they have also become "human," insofar as they have been mentally, spiritually, and morally transformed in their contact with humans. To give one important example, we see Captain Picard (a human) speaking to Lieutenant Worf (a Klingon):

Now, even when an individual or entire people have been baptized, their pagan past inevitably survives to some degree ... sometimes in a problematic way and other times in a harmless or even beneficial way (but most often somewhere in between). Examples where a Christian people's pagan backgrounds led to problems in the Church would include the adoption of torture by medieval European governments thanks to their reverence of ancient pagan Roman law which recommended it, or of the inequalities of the feudal system in Catholic Europe which descended heavily from pagan Viking influence. Examples where a Christian people's pagan backgrounds generally brought relatively harmless or even beneficial qualities could include the Irish Catholic retention of fairy folklore, Scandinavian monks recording the tales of Norse mythology, and certainly Christian Europe's preservation of pagan Greek and Roman philosophy. The Catholic Church has "baptized" many cultures, and more often than not, the baptized culture does not altogether forget their pre-baptized past. This results in a diverse array of cultures that nevertheless profess the same creed (whether it be Christianized Native Americans, Africans, Vietnamese, Arabs, Europeans, etc.). A similar phenomenon is seen in Star Trek, where diverse alien races have come together in communion thanks to humanity, and while they still have their own alien cultures (not to mention their own DNA), they have also become "human," insofar as they have been mentally, spiritually, and morally transformed in their contact with humans. To give one important example, we see Captain Picard (a human) speaking to Lieutenant Worf (a Klingon):

JEAN-LUC PICARD: CAPTAIN OF THE ENTERPRISE-D

"Being the only Klingon ever to serve in Starfleet gave you a singular distinction .... But I always felt that the most unique thing about you was your humanity. Compassion, generosity, fairness. You took some of the best qualities of humanity and made them part of you. The result was a man I was proud to call one of my officers."

|

|

Amidst all the differences between Christians of varying and unique cultures, the Church emphasizes that what is ultimately important is what they have in common, particularly their connection with God, which, in the end, puts aside all differences. As the Bible says, "There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus." In fact, Kirk's provocative line "Everyone is human" seems to reflect a similar kind of unifying vision. At the very least, Star Trek's acknowledgement of the differences between humans and aliens does not stop there. It ultimately seeks to unite. And yes, it is ultimately through humanity that it accomplishes this. Likewise, the Church in its diversity, largely thanks to its incorporation of pre-Christian cultures, is not ultimately about such diversity but about communion.

|

|

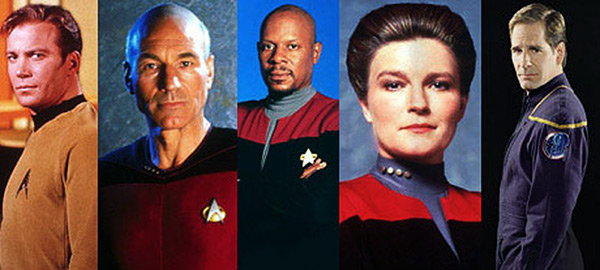

Every episode and movie in Star Trek features Starfleet, an organization of exploration, peacekeeping, and defense. Most members are human, but it also includes a diversity of aliens, albeit "humanized" ones. Starfleet is a constant in Star Trek and is "sacred." It is the Church, composed of both of "cradle Catholics" ("humans") and converts from pagan backgrounds ("humanized aliens").

The term "Church" can include any "Christian" or "Church Hierarchy" specifically (Pope, Bishops, Priests, etc.). Starfleet is the Church in the broader sense and other times the more specific sense, especially when pertaining to its hierarchical military structure. The word "hierarchy" itself, despite its secular usage now, etymologically means "holy order," having originally been used to describe the rule of priests.

Starfleet is often portrayed in microcosm within the particular ship/station that the protagonists inhabit. One might call each vessel a sort of small "c" church, which is fitting since the Church has often been symbolized as a vessel, something that carries and protects its passengers from what is outside it. Wagner and Lundeen even say:

JON WAGNER & JAN LUNDEEN: ANTHROPOLOGIST & SOCIOLOGIST

"Star Trek's project, in the face of this chaos, is one of establishing a 'fixed point' of orientation for the cosmos, and that point is the starship or station that carries its center with it in the otherwise decentered universe."

|

|

Despite the ultimate grandeur that both Starfleet and the Church attain in their respective histories, both had humble origins. Whether Zefram Cochrane (a lowly engineer from Bozeman) or Jesus (a lowly carpenter from Bethlehem), there would be an unprecedented establishment that would unite apparently disparate peoples that the world had not seen before.

The main goal of Starfleet is to explore space and thus achieve a higher knowledge more than would be possible if humans stayed on Earth. As Starfleet discovers time and time again, there are mind-boggling wonders to be uncovered in the infinite expanse, some at least bordering on the supernatural. The physical heavens have long been associated with the supernatural, the divine, and even the afterlife (hence the name ... heavens). Various early Christian thinkers speculated that the spiritual heavens (the afterlife) might in some way physically reside beyond the stars (beyond the "Empyrean" heaven, as it was known). You could say that the afterlife has very much been viewed as "the final frontier" or, as Shakespeare put it, "The undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns" (a line significantly referenced in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country). This classic idea of the supreme goal (the final frontier) being out beyond the confines of earth is very universal. It provided tremendous inspiration for men to study the heavens in the first place, generating a momentum that would eventually lead to modern astronomy. The sacredness of this celestial goal can be felt throughout Star Trek. The show gives the impression that Starfleet's space exploration is not merely for curiosity's sake, but for some higher end, one connected in some way to man's salvation.

The main goal of Starfleet is to explore space and thus achieve a higher knowledge more than would be possible if humans stayed on Earth. As Starfleet discovers time and time again, there are mind-boggling wonders to be uncovered in the infinite expanse, some at least bordering on the supernatural. The physical heavens have long been associated with the supernatural, the divine, and even the afterlife (hence the name ... heavens). Various early Christian thinkers speculated that the spiritual heavens (the afterlife) might in some way physically reside beyond the stars (beyond the "Empyrean" heaven, as it was known). You could say that the afterlife has very much been viewed as "the final frontier" or, as Shakespeare put it, "The undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns" (a line significantly referenced in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country). This classic idea of the supreme goal (the final frontier) being out beyond the confines of earth is very universal. It provided tremendous inspiration for men to study the heavens in the first place, generating a momentum that would eventually lead to modern astronomy. The sacredness of this celestial goal can be felt throughout Star Trek. The show gives the impression that Starfleet's space exploration is not merely for curiosity's sake, but for some higher end, one connected in some way to man's salvation.

As other commentators have argued, one might view the exploration of "outer space" in Star Trek as a symbolic exploration of "inner space" (that is, the "inner life" of man). The Barretts have argued this:

MICHÈLE BARRETT & DUNCAN BARRETT: LITERARY CRITICS

"The prologue of Star Trek tells us that the mission is 'to explore strange new worlds'. While this might be taken to refer to exploring space, we have suggested that it can be taken to refer to the exploration of human identity."

|

|

McKee makes the same conclusion, as well as connecting the traditional, spiritual perception of the celestial realm to the modern-day scientific investigation of the stars:

GABRIEL McKEE: THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO SCIENCE FICTION

"The ascetic practices of mystics and the rigorous training of astronauts are ultimately for the same goal, and the drive to explore the universe beyond our planet is the same as the desire to explore the inner life of the human spirit."

|

|

Despite the obvious differences between space exploration and spirituality, a surprising connection has nevertheless existed between the two. Starfleet, of course, strives for the former, while the Church strives for the latter, but they are not wholly disconnected. It hearkens back to the idea of "creation" being a reflection of the "Creator," and so through looking at the majesty of the universe, we can experience a faint but profound glimpse of the majesty of the divine. Being of this mindset, Johannes Kepler, one of the greatest and most renowned astronomers in history (and a devout Christian), said, "Since we astronomers are priests of the highest God in regard to the book of nature, it befits us to be thoughtful, not of the glory of our minds, but rather, above all else, of the glory of God." Here, Kepler explains that scientists (especially those who study the stars) are "priests," not in the literal ecclesiastical sense but as devoted celebrants of "nature," that is, of what God has made. Far from implying such roles are in opposition to the Church, he said they too ultimately must serve God too, just like real priests since all things have their origin in God. Therefore, in Kepler's mind, something like Starfleet, an organization composed of such "priests," would not only be analogous to the Church but might even be called a "Church" itself in regard, as he put it, "to the book of nature."

Despite the obvious differences between space exploration and spirituality, a surprising connection has nevertheless existed between the two. Starfleet, of course, strives for the former, while the Church strives for the latter, but they are not wholly disconnected. It hearkens back to the idea of "creation" being a reflection of the "Creator," and so through looking at the majesty of the universe, we can experience a faint but profound glimpse of the majesty of the divine. Being of this mindset, Johannes Kepler, one of the greatest and most renowned astronomers in history (and a devout Christian), said, "Since we astronomers are priests of the highest God in regard to the book of nature, it befits us to be thoughtful, not of the glory of our minds, but rather, above all else, of the glory of God." Here, Kepler explains that scientists (especially those who study the stars) are "priests," not in the literal ecclesiastical sense but as devoted celebrants of "nature," that is, of what God has made. Far from implying such roles are in opposition to the Church, he said they too ultimately must serve God too, just like real priests since all things have their origin in God. Therefore, in Kepler's mind, something like Starfleet, an organization composed of such "priests," would not only be analogous to the Church but might even be called a "Church" itself in regard, as he put it, "to the book of nature."

With all that said, some still object to there being a connection between modern science and Christianity. The Barretts apparently are two such persons ... but yet at the same time they simultaneously are forced to admit otherwise:

MICHÈLE BARRETT & DUNCAN BARRETT: LITERARY CRITICS

"The rationalism of modern western culture is of course oddly restricted by the fact that this is a culture throughout which religion, particularly Christianity, has flourished. It seems that people have learnt to live with this glaring contradiction. Indeed, modern astro-physicists, in their claims to see into 'the mind of God', are carrying on a long tradition of scientists adopting a 'priestly' role."

|

|

Even with the pro-religious Keplerian view of science, many scientists have not always been content to remain so-called "priests of nature" but rather have sought to abolish the "priests of God" and then to fill their shoes in addition to their own. Many times have we seen scientists arguing that Churches are outdated because ... "science!" far from complementing what they stand for, has allegedly disproved them. Such scientists step out of the traditionally defined limits of science into the traditionally defined role of religion, proposing not merely new theories about matter but also about morality and the meaning of life ... about what spiritual directions humanity should take. This is how Star Trek has often been interpreted ... that science has replaced theology in the spiritual and moral sphere. That argument can certainly be made. And again, strictly speaking, this does not weaken but rather perhaps strengthens my point, namely, that Starfleet is playing the role of the Church.

Aside from contemplation of the heavens, Starfleet officers act like missionaries. They are not content merely to observe "strange new worlds," "new life," and "new civilizations" but also to affect them. Starfleet's interstellar peacekeeping interests inevitably require this. As Thomas Richards notes, "The Enterprise is on a diplomatic mission, and the aim of diplomacy is not observation but intervention." What changes do they seek to establish this peace in the galaxy? As the Barretts claim, "in Star Trek the issue is to 'humanize' as many people as possible." The peaceful and fulfilling unity in the galaxy that Starfleet seeks is the same sort that unifies Starfleet itself ... its humanity. Starfleet is human at its core, and the aliens that join it do so because they have adopted human values (to varying extents). Those that refuse are almost invariably depicted as villainous and destroyers of peace in the universe. This can even include people who are technically human but failing to act like it (thus acting "inhumanely"). All this parallels the Church, which seeks to "Christianize" the world, both those who are pagan as well as those who are already Christian but imperfectly so. Those who reject this gift are tragically lost.

As mentioned previously, this unity in Starfleet and the Church does not abolish diversity. Starfleet, despite its human-centeredness, appears to be the most diverse organization in the galaxy. The Catholic Church, despite its one faith, is expressed through a large number of cultural variations. This is not to say that the diversity seen both in Starfleet and the Church is not without its tension. We see this in Star Trek perhaps especially with its humanized aliens, including its alien-human hybrids. Christianizing a people is often facilitated when already baptized Christians marry into their culture, similar to how humans and aliens having children together can facilitate humanizing alien races. Admittedly, such offspring often struggle to integrate their two respective backgrounds, sometimes being forced to choose between the two, that is, they must choose between "human morality" and honoring their alien heritage, not unlike converts who can find conflict between their newfound faith and their ancestral but occasionally problematic traditions. Without fail, it seems the show expresses that the human way (and the Christian way) is always better. The Barretts, perhaps rather cynically, note this as well: